Garage Days

Photos by Petruț Călinescu texts by Alex Axinte and Bogdan Iancu editing: Ioana Călinescu

“It’s like being on a warship”

This is what I hear from a birthday party guest in a garage in Chișinău – “Women don’t really come by here, I mean the wives. We’re free, no one here to pester us.” A crew of six or seven men are busily setting up the cramped space inside the garage for a blitzkrieg kind of party, in perfect sync, following a deeply-entrenched routine. Platters of food are unpacked, the fire for the shashlik is on, music is playing; I get invited warmly, though I’ve only just introduced myself fifteen minutes ago.

The setup reminds me of supra, the Georgian feasts where everything is laid out on the table from the beginning, from desserts to soups and appetisers, and glasses get downed with dizzying speed. The preparations – probably only comparable in length to the subsequent hangover – are all for the sake of a very quick encounter, during which everything on the table gets polished off hastily, without any pointless fuss.

The guests, in their 40s or 50s, are from all over the city of Chișinău, not just this neighbourhood. One dentist (ex-President Dodon’s dentist! as the others introduce him), two gentlemen who work at the customs office, the father of the birthday guy, who looks on fondly and indulgently as the hostilities ramp up. Two of the participants, who have just exchanged friendly greetings a moment ago, now hop around outside the garage with their hands clenched around each other’s throats. An older, unsettled conflict, nothing to worry about, they tell me – and, sure enough, the others have no problem completely ignoring the scene. Other than that, the mood is very merry; the dentist says, if he knew you could get free drinks just by showing up with a camera hanging around your neck, he’d have bought one himself. People laugh loudly; the two men outside come in, this time with their arms around each other’s shoulders like good chums. There you go, they tell me, the garage’s solved another issue, now they’ve made up; perhaps they wouldn’t have gotten over it without a garage to take care of things.

It’s been about two hours, and people are getting ready to leave; there’s a lot of leftovers, to be served tomorrow at a lighter, hair-of-the-dog get-together. I thank the hosts for having me and take my leave from everyone. One of the two men who almost got in a fistfight with his mate asks me to write down his phone number. Just in case something happens, I should give him a call. We may look like good guys, Petrică, but we can kick serious ass!

A place to pickle cucumbers/ make wine/ have barbecues/ hold parties/ store things/ tinker/ sell stuff/ give haircuts/ style ladies’ hair/ photocopy papers/ live

Dozens of thousands of garages were built in Chișinău, the capital city of the Republic of Moldova, during Communism. Later, in the transition years, they were joined by many other, illegally built ones. Huddled together in compact groups of several dozens to several hundreds or, in a few cases, even thousands, the garages outgrew their intended basic function and started to morph to adapt to each owner’s needs. Today, few of them continue to be mere places to keep your car. People pickle cucumbers here, store various things that change with the seasons, make wine from grapes on climbing vines (sometimes grown on the roofs of the actual garages), hold spontaneous or long-planned parties. The Mayor of Chișinău, too, was photographed drinking in a garage while playing improvised instruments; in another garage, two kilos of uranium were found. You can visit a garage art gallery, a fresh fish store or a museum for old computers, with about 100 functional machines as exhibits.

All the things you can’t do at home or out on the town you can do at the garage. Garages are privately owned or rented out. Most of them had a pit as well, meant so you could inspect the underside of your car. In some neighbourhoods, they got a second-storey extension and were fitted with saunas and everything you need in a small holiday home. The relatively low real estate pressure, the authorities’ willingness to turn a blind eye to unauthorised construction, and the fact that they are detached and, most often, far from the blocks of flats all made Chișinău garages a space for residents’ lives to overflow into, filling the small concrete cubes according to individual needs. Previous generations were more preoccupied with sustainability: the garages’ first owners broke through patches of concrete until they hit soil, then planted grapevines, set up trellises and “greened” their garages and their roofs.

Family moments at the garages

This year I returned to Chișinău after a long, pandemic-imposed break from my project. All the way there, I kept fretting. Will everything go well at customs, will they let me through quickly? Each time, the Moldovan customs officers came up with fresh reasons to peck a bit of pocket change off me; this time, pandemic and all, they let me through without any hassle. Coming from Romania, I find Moldovan roads eerily empty. With the stress about customs and traffic off my chest, I find myself almost alone on the road and wonder, the way I always do when I set out for fieldwork, what it will be like. Will I find people there, will there be any activity at the garages? Will they accept me among them easily, or will they at all? What will they say when I show them the photos I took last time? I decide to first try Lomonosov Street, where people have been very friendly in the past. Only a few garages are open, with what looks like a small family gathering in front of one. Holding my camera, I walk nonchalantly past the smoking barbecue, with a dumb smile plastered on my face, waiting for my inspiration to come up with an icebreaker.

“Come on in, we’ve been expecting you,” a woman wearing mourning black tells me as she lays the table. I go in, of course: In the small room, two families are sharing a massive meal, the table laden with salads and grilled meat. “This runt here’s to blame for the party; he told me he felt like a barbecue, so we got to work. We lost someone in the family recently. Have some more, try this one too. I knew you’d come. First a piece of meat fell off the grill. Then a beer spilled over. We figured, there you have it, the dead wants his share – so we knew a guest would show up to eat for him.”

The members of one of the families are just back for the summer holidays from Portugal, where they work. They pick blueberries on a farm there. They invite me to try some Portuguese blueberries from their harvest – the big kind, each the size of a grape. Any idea how much a kilo of these costs in Romania? I don’t, but for days to come Facebook will insist on informing me about various offers for buying blueberries in Romania. One of the children runs in and sticks a hand in the plastic box; in his hurry to go back to his play, he spills a few on the floor, among chunks of broken concrete. No one tells him off. His mother picks them back up one by one, washes them and puts them back in the box.

This life around the garages in Chișinău, though, made me think more of resistance than of poverty: We want to do things the way we know how, not the way they sell them to us. We want to eat and drink in our garage, not in a fast-food joint.

In Romania

The Garage, the Romanian's best friend

“Wherever you see Communist blocks of flats, you’ll find garages”

It’s the answer I get from a guy pottering about outside a garage in the town of Caransebeș, when I ask “Where else can I find garages around here?” His answer is correct, though only applicable to a certain type of Romanian small town. But for the monoindustrial settlements whose days of glory are long gone, it never fails. I roam the country, observing life around the garages built near blocks of flats, and every time I get to a new town it doesn’t take me more than a few minutes to find them. They are everywhere. I began my study of the garages’ social role in Chișinău, but the pandemic restrictions forced me to reconsider my route, so I set out to explore Romania. I started from the idea that a small garage fills a big need, which differs from person to person, but always fits into one of several broad categories: storage, socialising, DIY/tinkering/hobbies, summer cooking, and pickling or winemaking workshops. Other than keeping cars, of course, the utilities of the garage have long since expanded beyond its initial purpose, making it a place for anything you can’t or aren’t allowed to do in your flat. Still, in Romania the garage has not risen to the status of an institution, the way it has in the Republic of Moldova. There, blocks have a few garages – sometimes dozens – built near them. Their relatively low number compared to the number of flats gives their holders a feeling of subordination. Owners of apartments without a garage dictate what can or cannot be done at the garages. Mostly the “cannot” part. No grilling! (Alright, maybe sometimes, but not too often.) No noise! Other than storing things, garages can also be used for having a beer or two, as long as it’s on the sly. In larger towns, garages are almost completely gone. Development pressure has razed them to the ground, and people have found themselves with no place for their jars of pickles.

The people around Romanian garages seem to live with a feeling of guilt. They keep trying not to disturb their neighbours, so they won’t get public order complaints. Indeed, many are very suspicious. When I show up with a camera, most of them are afraid I’ve been sent by someone to record them doing something illegal. Where there are no vacant lots for new developments, garages are the first to be demolished to make room for future buildings.

From the ancestors of current garages – the ones made of wood in the north of the country (like Sighet, where they have an upper storey and rooflights) – to the typical concrete cuboid, the ones made of recycled materials, or the few exceptions featuring stylish refurbishments (one was turned into a café in the Dorobanți neighbourhood of Bucharest), garages in Romania hide the poverty of the small-town population. There is no room for hobbies in a garage crammed with firewood – many blocks of flats in such towns have been cut off from the cetnralised heating grid, and they are not connected to the gas grid. Where there were no garages, locals improvised something closer to sheds where they keep firewood to take care of heating as best they can. In Orșova, the heating plant of the one neighbourhood with blocks now hosts the church of a new cult.

People store survival goods in their garages: food brought over from the house in the village, pickles, preserves. The main activity near them seems to be transporting various goods to and from the garages.

“Probably the happiest times of my life”

In the silent scenery of locked-up garages, lined up tidily, blanketed in the carbon dioxide from the wood-burning stoves heating the flats and oozing smells of fried fish with crushed raw garlic, two old-age pensioner ladies in Caransebeș cook and have their lunch in a garage with doors wide open. Decorated with party balloons, fitted with a professional grill (works with both gas and coals, has a lid, was brought as a gift by the children working abroad), electricity, a fridge and water on tap, the two women – friends and neighbours – whip up a semblance of fine living out of their meagre means. One of them is very shy and prefers to let her friend, the owner of the garage, tell me their story. They are widows who spent their adult lives working at a local factory, now closed down. The garages were built by the factory for its workers living in the blocks nearby. Since they are on the edge of town, the garages are fated to be demolished if any developer takes an interest in the area – as their garage neighbours fearfully told me. Nonsense, comments Mrs. M. when I ask if they, too, are afraid they’ll be left without their garage. She’d rather focus on frying the fish than burden her mind with negative scenarios which she has no power over anyway.

Her phone rings and she launches off in a long videocall with her daughter, who is away working in Germany. I get introduced, wave at the camera, explain what I’m doing there – she is curious about how the press has ended up in her mother’s garage.

Meanwhile, the mămăligă steams on the plates and the fish is already drenched in the raw garlic sauce. I thank the ladies and try to leave and let them eat in peace. But they won’t hear of it and insist until I sit down. While I’m there, I help them get out the cork stuck in the neck of a bottle of homemade brandy, which makes me feel useful and less guilty for invading their private space.

Garages for blocks of flats

Closed, semi-open, and open

by Alex Axinte

Context

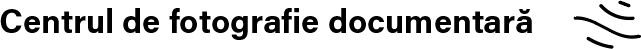

Context On the 20th of August 1968, the gates of the Automobile Plant in Pitești opened to let out Dacia 1100, the first car assembled in Romania. Before long, in 1969, it would be followed by Dacia 1300, the first car made entirely in Romania, both after French patents. The Dacia brand –shrouded in nationalism but fitted with Western technology – was intended to be a “car for the working man” [1]. It ended up more of a product meant for the emerging Socialist middle class, which had started to manifest needs for non-essential comfort goods and an accumulation of income and resources superior to previous times. Along with the other privately-owned cars imported from other Socialist countries in the streets of Romanian towns, Dacia would contribute to a new function associated with collective living: the garage.

As early as 1966, citizens could own homes [2], through a system of state loans paid back in instalments. Around the same period, the types of flats in the collective living blocks multiplied and became more generous (Stroe, 2015). Thus, architectural concept sheets began to take into account the proliferation of household appliances and the diversification of the occupants’ habits and interests. Though almost always insufficient and supplanted by other functions, such as the balcony or the vestibule, storage spaces expanded. They sometimes benefitted from favourable circumstances, when designers managed to apply them, despite the standardisation and austerity policies that imposed drastic limitations.

In the’60s, the great neighbourhoods of blocks of flats were built after the model of the micro-raion, consisting of “complex urban planning units”, scientifically planned, where each architectural programme (habitation, education, commerce) had its own building (Rău & Mihuță, 1969). One of the shortcomings of this model was the lack of privacy of flats on the ground storey. Various solutions were debated and tested (Caffe, 1987), such as raising the ground floor level a few steps above the ground, or placing household annexes at the ground or underground level, other than commercial or service-providing spaces. This ushered in the basement storage units, for the goods in the apartments above, and the garages, for the privately-owned cars.

The hypothesis according to which garages appeared as a programme associated to collective living relies on a fortunate conjuncture in which the stars aligned in favour of storage spaces. Thus, the need for comfort and the higher financial possibilities of the emerging middle class were combined with economic growth, supported by the progress of prefabrication technologies and facilitated by the generous explorations of the period’s designers for improving living conditions. This window of opportunity would close after the mid-’70s, as the economic crisis set in and garages disappeared from the ground level of newly designed blocks. What did not disappear, however, was the need for extra storage space and the housing industry’s capacity for prefabrication. So it is that, in the ’80s, garages begin to be built on public land. Sometimes made of wood or sheet metal, but most often built of precast concrete [3] or a hybrid combination, laid out in “rows”, “alleys”, or “batteries”, they would become a familiar part of the view in neighbourhoods of blocks. Garages would continue to be built in the courtyards of blocks in the ’90s, but would gradually be evacuated by the paradigm of growing civilised after the 2000s.

Garages in the Loop

Prior to 1989, the number of privately-owned automobiles was not very high [4]. For example, the norm for outdoors parking spaces applicable to urban plans until 1989 provided one parking spot for every ten apartments. Still, as prefabrication took hold, architectural solutions for blocks with garages at the ground level became far more generous. With commercial functions placed at the periphery and educational functions placed centrally (Revista Arhitectura, 1970), in micro-raion 7 of the Drumul Taberei neighbourhood (or the Loop, as the locals call it), about 15% of buildings meant for housing have garages at the ground storey. All of them replicas of the same project, these low (ground + five stories) buildings each have 54 garages for 60 apartments. As they came as annexes to the apartments offered for sale to the population, garages had to be paid “upfront” by their first owners. As the people did not have a car or were waiting for their long-placed order, many of the garages became a resource of storage space. With an inner surface area of 5x3 metres, connected to the water, electricity, and heating grids, garages became workshops, pantries, places to meet, relax, play or pursue hobbies, according to a local’s memories of garage life in the ’70s-’90s:

It is an amazing way to get out of the heat and crowdedness of the apartment. You get down there and are sort of in nature. That matters, at least to me it matters a lot. ... There is vegetation [between the garages] but you just sit around in the open and have a chat with your neighbour and whatnot. It’s something completely different. I can’t stand the idea of living in a flat, though until I was 25 I had only ever lived in one. I can’t stand it anymore, the walls just squeeze me in. I find these spaces extremely versatile. You can do a lot in a garage like this, things you can’t do in an apartment. In an apartment, if you have a bedroom, you have to sleep in it and that’s all. Maybe you can have friends over. But in a garage, imagination is free to fly. (I.C.)

Also before 1989, garages were legally separated from the apartments. As they started to be listed in the land register separately, they were borrowed, rented out and even sold, to the extent that such a thing was possible at the time. After the Revolution, they saw “improvements” (floor tiles, double-glazed windows, plasterboarding) and were sold independently on the real estate market. [5]. The garages’ material transformations included extensions (awnings, canopies) which often marked the opening in some of them of small commercial and service-providing spaces (Staicu, 2013).

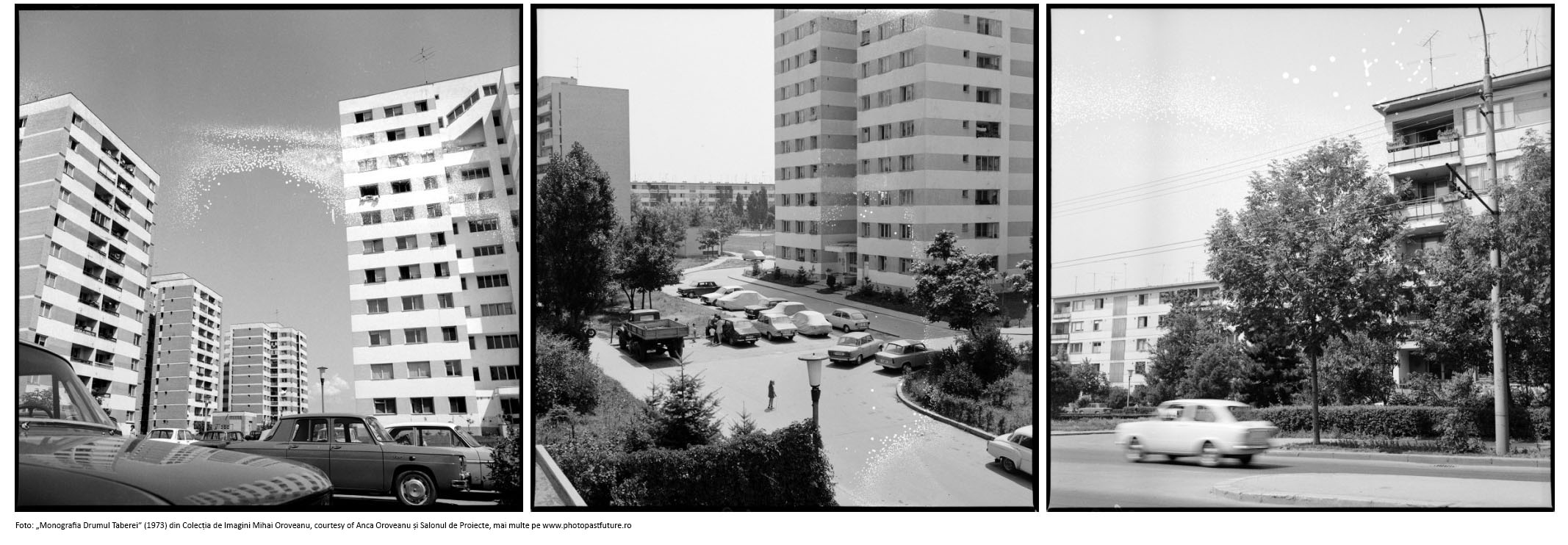

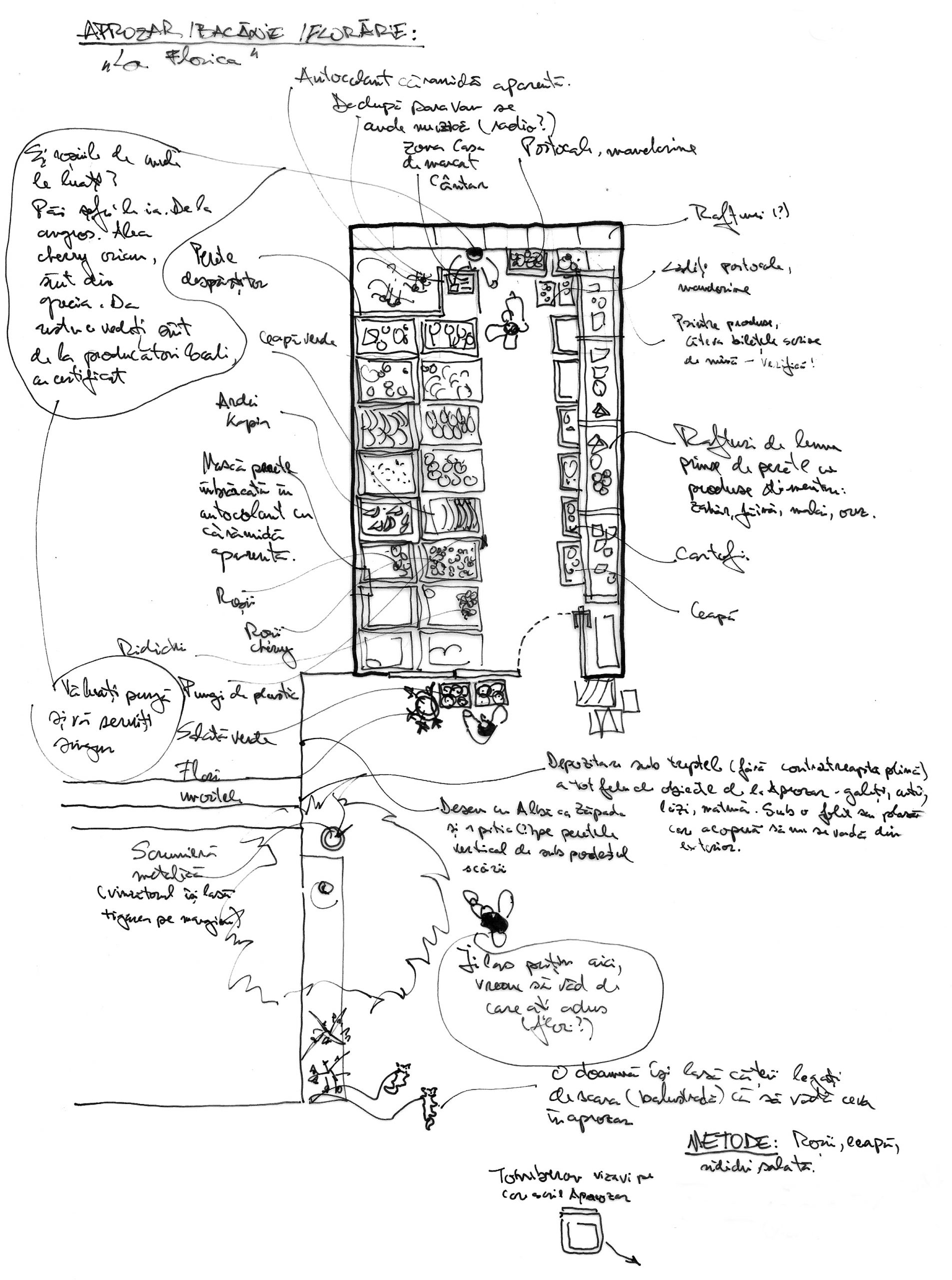

Following the recent mapping of garages in the Loop [6], apart from those used exclusively to keep cars, a few typologies have been outlined: 1. Open garages (commercial and service-providing) with grocery or fruit-and-vegetable stores, or shops selling wine, car parts, sanitary ware, as well as tailors and cobblers’ workshops, barber shops, or veterinarian or optician practices. 2. Semi-open garages (closed-circuit) used by friends and acquaintances as places to meet, socialise, have a barbecue and a beer together or provide private tutoring for pupils, guitar lessons, do rehearsals or DJ sessions. 3. Closed garages (in private use) used as domestic extensions of the flats above, to store furniture, sports gear, bicycles, pickles, canned fruit, jam, or as DIY workshops, gyms or play areas for children.

The space in front of the garage becomes an extension of its function, to be used according to the owner’s choice. As it has more or less the same size as the garage, it can be used for parking. However, for open garages in commercial or service-providing use (less than 5% of the total number of garages in the Loop), the perimeter outside doubles as advertising space and as a place for displaying goods or just relaxing. In front of semi-open or closed garages, too, games or hobbies liven up the surroundings, as locals practice “going out to the garage” as a form or relaxation and interaction with neighbours, taking part in community life. The interior and exterior repurposing of garages have turned them, in places, into nothing short of informal neighbourly socialising spaces, answering the acute need for such areas in neighbourhoods. Still, their proximity to the windows of apartments, their various public uses in areas that can “draw customers” and some legal ambiguities resulted from deeds of inheritance sometimes make garages objects of contention between neighbours.

Strips of spare rooms

In his book Locuirea urbană [Urban Housing] (1985), architect Peter Derer – relying mostly on Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon references from the period – criticises the functional segregation of urban planning models for the micro-raion unit. The study proposes (both for neighbourhoods currently being planned and for the transformation of existing ones) the principle of “residential generators”. This approach aims to integrate habitation and functions into “communal use strips” providing services, commerce or leisure. This entire strategic endeavour relies on “residential composites” including semi-autonomous spaces attached to residential buildings. Called “spare rooms”, these spaces are proposed as a solution to the low flexibility of flats in blocks and to the lack of spaces for studying, hobbies or communal use.

The impact of the book at that time probably never went far beyond the academic sphere, with no effects on the production of housing, which was dominated by the austerity paradigm. But its proposals reflect the interests of some designers of the age [7] who were attempting to go beyond the schematic, quantitative approach of the micro-raion or the simplistic solutions of “densification” and “linear positioning” and towards a more nuanced, more dynamic, more flexible dimension encouraging spontaneous neighbourly interactions and, through “supportive structures” (Derer, 1985), the participation and contribution of inhabitants to the transformation of spaces in neighbourhoods.

The book can be considered visionary for the time when it was published; indeed, it reflects in technocratic language phenomena that were already apparent at the grassroots in block neighbourhoods. A whole slew of informal practices – from closing off balconies to improvising gardens or building canopies – implicitly supported the principles of the “residential generator”. In this context, garages basically acted as “spare rooms” for their owners, contributing to the outlining of “strips of communal use” within micro-raions with no facilities, services or spaces for neighbourly socialising. In the absence of projects of urban regeneration for block neighbourhoods, garages were a solution for various categories of inhabitants who had no other alternatives. Moreover, they became resource spaces in the invisible neighbourly mutual aid and exchange networks.

Despite their vulnerability to the excesses resulting form public use and real estate transactions, with the support of firm public policies dedicated to the situation on the ground some of these garages can also become an explicit community resource. Thus, they can gain a more active role in consolidating a network of open civic, educational and cultural spaces at the heart of urban areas where such functions are entirely absent.

1 Adevăruri despre trecut: Dacia, luxul epocii de aur [Truths About the Past: Dacia, the Luxury of the Golden Age], TVR (2018).

2 Decision 26/1966 of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party and the Council of Ministers of the Socialist Republic of Romania on support provided by the State to urban citizens in the building of

privately-owned homes (Stroe, 2015).

3 The most widespread was the prefabricated reinforced concrete model called “Granitul”.

4 Many local cars were built for export, so waiting lists took years to be filled, as costs were

quite high.

In 2021, the running price for renting a garage in the Loop ranges between 50 and 200 euro (depending on its use), while the sale price varies between

15.000 and 20.000 euros.

6 The field research was carried out between November 2020 and September 2021 and was initiated by Alex Axinte as part of his doctoral research at the Sheffield School of Architecture (SSoA), University of Sheffield. He was later joined by Iris Șerban, Bogdan Iancu, Anca Niță, Ileana Szasz, Diana Culescu, and Ioana Tudora, as the project took the form of Harta Practicilor Colective [the Map of Collective Practices], the exhibition titled Drumul Taberei – Cartier Deschis [Drumul Taberei – Open Neighbourhood], and four documentaries (dir. Ileana Szasz) produced as part of the Garaj DESCHIS [OPEN Garage] project.

7 In the’70s and ’80s, many field research studies were carried out on collective living as part of the Laboratory for Sociological Studies and Research of the Institute of Standardised Building Design (IPCT).

Bibliography

Caffe, M. (Ed.). (1987). Locuinta Contemporană. Probleme Și Puncte de Vedere. București: Editura Tehnică.

Derer, P. (1985). Locuirea Urrbană. Schiță Pentru o Abordare Evolutivă. București: Editura Tehnică.

Rău, R. & Mihuță, D. (1969). Unități Urbanistice Complexe. București: Editura Tehnică.

Staicu, M. (2013). Amprente…: o incursiune antropologică asupra locuirii din marile ansambluri. Cazul Drumul Taberei. Bucuresti: Editura Universitara „Ion Mincu.

Stroe, M. (2015). Locuirea între proiect și decizie politică: România 1954-1966 = Housing, between design and political decision-making: Romania, 1954-66. București: Simetria.

TVR. (2018). Adevăruri Despre Trecut: Dacia, Luxul Epocii de Aur. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pP39ir34EMc

(1970). Revista Arhitectura. , (1).

Text based on the written research done during the project OPEN GARAGE, follow the link for more details: https://www.facebook.com/garajdeschis

Drawing by Alex Axinte

The Grocer's

We first stepped into one of the two grocery shops in the Loop one Sunday before lunch, to buy strawberries. The lady who seemed to be in charge abandoned a conversation outside the neighbouring shop and came in after us. When we told her we wanted to have the strawberries right there, she called us to the back, where a tiny sink was crammed in. When we returned a few days later, her son-in-law was standing in for her at the teller and in the banter across the border with the neighbouring shopkeeper. We wondered again, aloud and in the presence of the owner, at how well-equipped the tiny space was.

‘I’ll have you know I invested 12.000 lei in getting this grocery shop set up, it had nothing of what you see here when I took over.’

There follow price details for each individual component, from the floor tiles and the double-glazing windows to the lighting to bring out the aspect of the fruit, vegetables and preserve jars.

‘I have the fruit and veg from my mother-in-law’s farm (note: the lady we met in our first incursion), we produce them in a village by Găești. That’s also where we preserve the bitter cherries, peaches, beetroot with radish and pickles.’

‘I have the fruit and veg from my mother-in-law’s farm (note: the lady we met in our first incursion), we produce them in a village by Găești. That’s also where we preserve the bitter cherries, peaches, beetroot with radish and pickles.’

‘Next time bring some serious tupperware and I’ll get out some for you, wait and see how tasty they are.’

Somewhere outside we hear dice hitting wood, then a firm hand shifting a few checkers around. Indeed, each time we would later pass by, we’d find the backgammon board set up on tall stands, right on the borderline, between the grocer’s and the neighbouring shop; most likely, nothing but the rain, snow or freezing cold can move it from its place.

Text by Bogdan Iancu

Drawing by Alex Axinte

The Convenience Store

The convenience store has been, throughout our research, a helpful stop both for socialising and for the lunches we had to improvise for ourselves in the neighbourhood. The owner, Mrs. Cristina, can always be found just outside, on a small stool, having a smoke and a coffee with her neighbour, the lady from the optician’s. Around spring, when we first came in hunting for sandwich ingredients, Mrs. Cristina warmly recommended the range of coldcuts labelled simply “brought from Székely Land”: parizer, sausage, salami. If she was out of any of them, we were assured that her husband, who handled supplies, would restock them in a few days.

Another flagship range of the mini-store is the canned fruit, jams and sheep’s yogurt (in a jar) which they import from Bulgaria:

‘We have our source in Ruse, a direct provider. They’re amazing, next time you stop by do let me know what you thought of them.’ The two ranges are accompanied by the food cooked by Mrs. Cristina on order, mostly just for locals from the Loop: sarmale, cutlets, chicken liver paté in plastic casseroles, Russian salad, fish roe spread, soup, cakes. She takes orders for the major holidays – pască for Easter or various coldcuts for Christmas and other major events. Mrs. Cristina got her special training back when she worked at the Military Hospital, cooking for the cafeteria there. A few streets away, someone else in the family – her daughter – has just opened a barbershop.

by Bogdan Iancu

Drawing by Alex Axinte

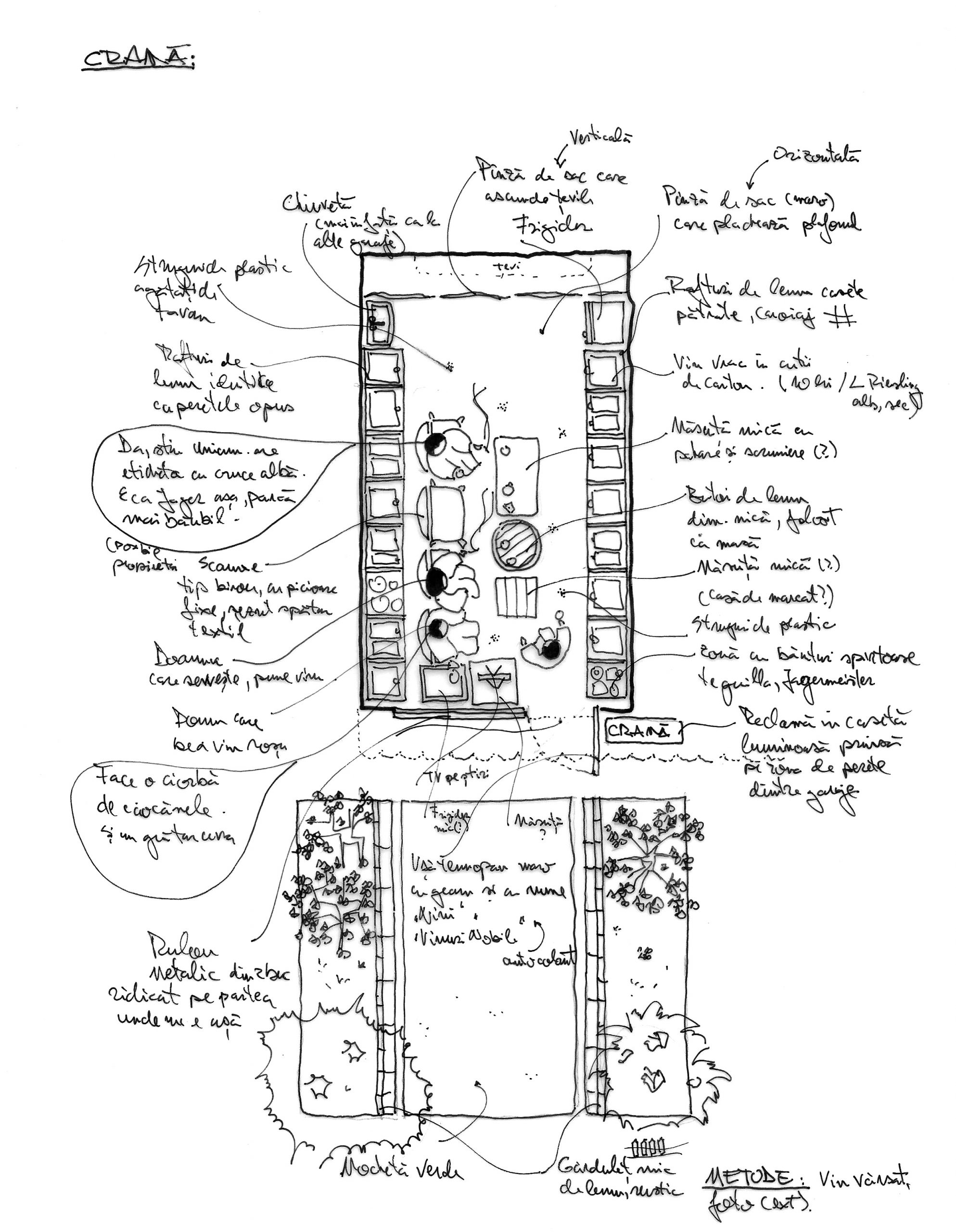

The Wine Shop

A quaint interior, with sackcloth hanging from the ceiling in waves, a light fixture made to look vintage, plastic grapes hanging from the sackloth, metal shelves laden with bottles and bag-in-a-box wine sold by the litre. The centre is taken up by two low tables and a barrel, also used as a table. The zesty smell of a well-frequented pub.

‘Want some by the litre? If you’re looking for something more special, I have the kind that comes with a corkscrew, for 20 lei.’

Seated on office chairs, a few clients/friends are testing the merchandise and chatting. The lady behind the counter pours the wine into a former cola bottle and watches the TV with the sound turned low. A gentleman stops just inside the doorway, having left his shopping trolley outside.

‘I’m making chicken drumstick soup today, then a barbecue or something.’ The entrance to the garage is flanked by a low, rustic-looking picket fence. On the side wall there is a neon sign reading CRAMĂ [Wine Shop]; on the door there is a sticker reading “Vinuri Nobile” [Noble Wines]. Outside, on the alley, a neighbour is walking his dog.

by Bogdan Iancu

Camera Suplimentară [The Spare Room] (dir. Ileana Szasz, 2021) – a short documentary on the things that happen in the garages and their role in the life of the sprawling block neighbourhoods, with the Loop in Drumul Taberei as a case study, produced as part of the Garaj DESCHIS, for more details: https://www.facebook.com/

Speakers:

Corner shop: Coca Apostol

Hobby workshop: Gabi Dinu

Thanks to: Coca Apostol, Gabi Dinu, Georgiana Trif, Călin Ionașcu, Cristian Ionașcu.

Interviews by: Alex Axinte, Iris Șerban, Ileana Szasz

Camera: Ileana Szasz

Video edit: Alexandra M. Diaconu

Photos:

Petrut Călinescu/ Cdfd

Texts by:

Alex Axinte – architect and researcher with an interest for collective practices in the context of collective living in post-Socialist cities. Having graduated from the Ion Mincu Architecture and Urban Planning University (UAUIM) in Bucharest in 2004, he got his MA in Social Research in 2018 at the Sheffield Methods Institute (SMI) of the University of Sheffield. He is currently preparing his doctorate at the Sheffield School of Architecture (SSoA) of the University of Sheffield. Alex is the co-founder of studioBASAR and the initiator of the Garaj DESCHIS project.

Bogdan Iancu – university lecturer in the Sociology Department of the Political Sciences Faculty of the National School for Political and Administrative Studies, where he teaches Visual Anthropology, Ethnographic Practice, Material Culture, and Sociology of Daily Life; researcher at the Museum of the Romanian Peasant in Bucharest. In 2011 he obtained his Ph.D. in Anthropology and Ethnology from the Università degli Studi di Perugia.

Texts editing:

Ioana Călinescu/ Cdfd

Web developer:

Dani Ivan

A project co-financed by the Bucharest Municipality through ARCUB as part of the București – Oraș deschis 2021 Programme, by the Romanian Order of Architects (OAR), through the architecture stamp duty, and by the Administration of the National Cultural Fund (AFCN).

The content of this website does not necessarily represent the official position of the Bucharest Municipality nor of ARCUB. For more information on the financing programme of the Bucharest Municipality as mediated by ARCUB, please access www.arcub.ro.

This project does not necessarily represent the position of the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. The AFCN is in no way responsible for the content of this project nor for the potential uses of the project results. The responsibility for the latter lies entirely with the beneficiary of the financing programme. RO-EN translation by Anca Bărbulescu